Rick Danko found Big Pink as a rental in 1967. He was 24 years old when he first set eyes on what would become Bob Dylan and the Band’s back-to-the-land Camelot. By the time of Music From Big Pink’s 1968 release, Danko had developed his signature staccato sound.

Richard Clare Danko was born in Blayney, Ontario, a small farming community roughly halfway between Detroit and Toronto. It was a musical family — his father played strings, and his three brothers would become musicians as well. He grew up listening to the radio, citing “…Hank Williams, country music, Sam Cooke, rhythm and blues, Little Richard, [and] Fats Domino” as early influences. At 14, Danko dropped out of school to pursue a career as a guitar player. He landed a gig in Ronnie Hawkins’ outfit, The Hawks, a few years later.1

Then, like so many great guitar players, someone asked him to play bass.

On Note Length

In the late 1950s, the first generation of studio professionals using the electric bass started inserting foam and felt into the bridge to remove sustain and overtones. These studio musicians were transitioning to the much more portable and playable electric bass, but trying to do so in a way that retained some of the sound characteristics of the upright, which dominated the music of the first half of the 20th century. The upright bass is a huge instrument. But despite its size, the notes don’t sustain as long as the amplifier-assisted electric bass.2

However, as the 50s turned into the 60s and beyond, the foam/felt mute fell out of common practice. Rock music boomed and continued to flourish, leaving the aesthetics of the upright in the past. Music got louder and more distorted, and so bass players removed their mutes in order to keep up.

The point of this is to illustrate that note length is and has always been one of the primary considerations of playing the electric bass. Obviously, the sound of the muted bass didn't disappear, it changed. The palm mute gets the job done for most - it’s easy, the sound is 90% the same, and it requires no modification to the instrument.

Regardless, I’d bet the farm that all great bassists have developed their identity by way of note length. Like any other major identifying factor, it’s part culture, part practice, and part personality. Furthermore, I would go so far as to say that Danko’s primary identifier is note-length. As such, think his sound is sourced from three places in the Americana tradition, having to do with the beginning, end, and placement of his notes:3

In popular music, the use of the tuba and specifically the two-feel as played by the tuba — e.g. sliding into a note + a quick release.

In hillbilly music, the sharp click of the front end of a string bass — e.g. the sound of strings smacking against the fingerboard, which Danko often reproduced using a pick.

In mid-century radio R&B, the syncopation and rhythmic vocabulary of the Black music tradition in America - e.g. the primacy of rhythm, forward momentum, swing, syncopation.4

Together, these three elements make up the basic aesthetics of Danko’s bass playing.

THE TUBA PT. 1: POTATO HEAD BLUES

Before the electric bass there was the string bass, and before the string bass there was the the tuba. Early New Orleans music is a good place to look for an example of the tuba filling the role of the bass outside of classical music.

Here’s Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven; fundamental DNA of American music and also a good example of tuba-as-bass. Recorded in Chicago! Pete Briggs playing tuba.

Notice how quickly these notes end. It takes a lot of air to make any kind of sound on a tuba, not to mention playing with the pocket and volume required to accompany Satchmo at the peak of his powers.

Also, notice how Briggs’ attack sounds: he does a small-scale slide into some of his notes, rather than just hitting it straight like a piano or bass guitar.

THE TUBA PT. 2: BALLAD OF A THIN MAN

From Before the Flood. Recorded at LA Forum in Inglewood, CA during Bob Dylan and The Band’s 1974 American tour. Dylan’s Planet Waves was recorded right before this tour and Blood on the Tracks was recorded right after.

Outrageous forward momentum coming from this rhythm section. Arguably the most important band in the history of rock music at the top of their game. They couldn’t make a mistake if they tried. Are they serious? Are they not? Bob Dylan is completely unfuckwithable. Danko is on fire.

Danko’s short note length brings to mind Pete Briggs’ tuba. Short powerful notes are driving the forward momentum of the song.

I love this whole bass performance, but at the 2 minute mark Danko holds the whole song in his hands. His bass fills are always in the right place; you can tell he was 1) always listening to the melody and 2) experiencing the melody in real time. He marks the chorus’ transition with a fill, playing just one note repeatedly, sliding into it every time just like the tuba.5

While we’re here, I want to draw quick attention to what is possibly my favorite bass guitar intro of all time: “Look Out Cleveland.” Here’s me playing it last year:

No one else would dare! The first half sounds like something that would come out of a Sousa march. The second half is really just basic bass vernacular, something he would have heard Jamerson, Kaye, Jerry Jammot, and/or Duck Dunn play on the radio 1000 times. But here, Danko has his own sauce on it.

STRING BASS PT. 1: COUSIN JAKE

Next, we’re going to take a look at the hillbilly element… Check out Cousin Jake and Earl Scruggs below, and pay particular attention to Cousin Jake’s right hand.

Today, it’s mostly rockabilly guys who look like Guy Fieri that keep this open palm slap style going, but in the earlier half of the 20th-century, it was a mainstay of bass playing.6 Cousin Jake is a master of it. “No hands!!!” He’s pulling the strings of the bass out and letting them smack up against the fingerboard to make a loud clicking noise. Danko’s translation is the click of the plectrum.7

STRING BASS PT. 2: RING YOUR BELL

I could basically pick any recording for this, but I want to showcase one of my favorites from Northern Lights - Southern Cross.

Man could he play an intro! Everyone sounds great. Danko benefits from the increase in recording fidelity as the 70’s roll on, as we can make out more of the pick noise in his tone.

The click of the bass is LOUD. Here, the bass guitar is surely functioning as a drum too. You can definitely hear the sound of Cousin Jake and hillbilly music floating around in the consciousness of this recording.

THE SYNCOPATION AND RHYTHMIC VOCABULARY OF BLACK MUSIC IN AMERICA

All of the above examples of Danko’s playing contain syncopation and the rhythmic vocabulary of Black music. Listen to a moment of this:

Rhythmic language is difficult to talk about due to the availability of helpful semantics — for example, try to describe what “feel” is — but to state the obvious, Danko did not learn how to play bass like this by listening to the Carter family. He learned by listening to “Sam Cooke, rhythm and blues, Little Richard, [and] Fats Domino.”8

If the two previous sections were about the length and attack of Danko’s notes, this is about where he is putting those notes.9

ON DEVOTION TO THE TRADITION

Robert Doerschuk, writing about Danko’s final performance at The Ark in Ann Arbor, MI in 1999, says this:

For maybe an hour he sang, accompanied by his longtime pianist and accordionist Aaron Hurwitz. His voice was rougher than on the old records, and noticeably lower. In playing some of the tunes he had helped immortalize years before — "Chest Fever," "Shape I'm In," "Stage Fright" — he pinched on many of the high notes which he had picked off cleanly and clearly years before. But there were moments when he locked onto a lyric, or made those magical leaps up half an octave where you least expected it in a melody, that stirred memories from a time when Danko and his colleagues in the Band were at their prime — when they were virtually the only act playing for young audiences in the '60s that didn't flounce like superstars or turn their backs on unhip aspects of Americana tradition. (emphasis mine)10

As Doerschuk notes, Danko never turned his back on the unhip parts of the tradition, and that is what ties his playing together. Here’s Danko and Levon playing straight-ahead music with Lenny Breau:

Damn they sound good! Absolutely no surprise that these two can swing, but this is outrageous. Danko doing the Charlie Haden repeating notes in half-position thing??? Two of the baddest hillbillies in history. Levon is actually unbelievably great and knows his Philly Joe Jones. They really know their shit! They sound correct. I would love to hear one of the infinite Last Waltz tributes stumble their way though “It Could Happen to You.”11

Danko’s first gig was playing a wedding when he was a kid. Before he was a rock star, he was a working musician who played a variety of styles. In this recording you can hear that to Danko and Levon, It’s not good enough to just be able to gesture at other musical forms and traditions. You have to know how to play them correctly. The tradition mattered to The Band; this is devotion!

Many musicians, in my opinion, have an idea that becoming great requires some kind of nebulous, individual access to “truth.” Studying the old masters, like Danko, makes me think this is misguided. It’s not that nobody knew Danko’s influences — everyone did. It’s just that they thought those influences were lame!

It’s not that Danko was the only one to hear the tuba as bass, or the click in the bass of hillbilly music, but his playing expresses he really was devoted to these sounds. Carrying on these aspects of the tradition was part of his aesthetic value system - he showed his devotion to the tradition by way of emphasizing these sounds.

For example: nobody gave a fuck about tubas in 1976. But Rick Danko did, and that’s part of why we remember him now. Once again: It’s not a question of resources; it’s a question of devotion. We find our own voices by studying the tradition, and the tradition values devotion above all else. Music is culture and history in practice. Lame one-liner but it’s true!12

DANKO HOTLICKS

Rick Danko teaches bass. This is barely an instructional video (and it looks like it was filmed with a toothbrush), but from what I can tell, this is Danko’s only foray into the debauchery of American rock music’s instructional DVD era.

The very first thing he plays is a shuffle. This is not a hip shuffle! This is a tent revival shuffle. Danko’s through-line is sounding good on any music traditionally played under a tent. This is a shuffle that I or anyone else would be made fun of for playing on a rock gig today.

There’s some kind of profound rhythmic information being passed along here. This/the shuffle is a fundamental building block of popular music. It’s almost as if Danko is saying “this is what you need to know; after this, everything else is your own making!”

I think one of the many dangers of the algorithm is that it is putting distance between us and the tradition, and filling up that cultural space with a commodified refraction. Social media silos prioritize the shiny and cool, but nothing that’s culturally really important is ever that far from being kind of lame. We have more access to information than ever before, but the permeation of social media into the functions of our daily lives prevents us from forming real, meaningful relationships with that information.

For instance — How many rock musicians today can really, truly play a shuffle that feels CORRECT? I’m generalizing here, but by and large, much of the rock revival/indie-rock music that is going for the sound of The Band is pretty fucking bad. To me, this is evidence of a lack of a personal relationship to the tradition. For instance: Danko and co. could play both their music and the tradition, and they knew the difference between the two. In my experience now, most people in rock music only know how to play their own music.13

I don’t mean to sound like a cynic! This is not the most important election of our lives. I believe every generation of musicians is in conflict with the technology of their time. Think of Louis Armstrong, who 100 years ago probably recorded “Potato Head Blues” into a single microphone.

But today we are in conflict with the algorithm and social media. I’m not suggesting that the ‘missing element’ to music these days is that we all need to memorize as much of the old music that we can, even though that would not be a bad thing! No amount of playing “Fiddler’s Wheel” etc. makes anyone into The Band.

My point is that the reason that Danko was/is so great is because he cultivated a personal relationship to the tradition over the course of his musical life. So often, the ways that we engage with the tradition now have been pre-narrativized and pre-commodified to go down easy - i.e. click this link to get 200 free 2-5-1 licks for the bass guitar. The tradition is our musical “third space,” and like our real-life third spaces, it is being wrested from us by tech companies and corporate interests.14

The players have changed but the fundamental game is the same! This lyric from Joni Mitchell’s “Edith and the Kingpin” comes to mind: :

Sophomore jive

From victims of typewriters

The band sounds like typewriters

Danko and The Band didn’t sound like typewriters. They had real relationships to the tradition and understood their own place within that continuum. They could channel the unhip parts of the tradition while also staking their own claim in the present.15

This has been fun! See you next time. Here’s a live recording of my favorite off the self-titled record.

LOOSE ENDS / TANGENTS

There’s a big argument going on in the background here about the 3 over 4 American beat, and how we’re rhythmically straightening out over time. I do not know enough to articulate it but maybe in the future!

Note on technique: while writing this, I realized that for a lot of his recorded music (especially later in the 70s), there’s an argument to be made that he's not really muting everything in the right hand like most people assume. Instead, he's cutting everything short in the left. His left hand is very surgical; his right hand is more fun. He is playing like this in the instructional video as well.

On tour last year, Jeff Tweedy told me that Uncle Tupelo toured with The Band in the 90s once. The Band crashed one of UT’s rehearsals prior to tour, and Danko stood behind Tweedy while he played and sang. After explaining to Danko that no one can reasonably expected to perform well on a bass guitar under those circumstances, Danko approvingly reassured Jeff that he “sounded desperate.” There is a lesson in there. Obviously we know that Danko sang desperately, but there’s something about his playing where he is emptying the tank 100% of the time.

Doerschuk, Robert. "Rick Danko." Van Cliburn Punched Me In The Mouth. Last modified January 20, 2021.

The tiny little my-parents-went-to-college bass mutes I see about town are not functioning the same way the heavy mutes of the 50’s did. A small mute kills overtones and prevents unwanted finger noise, but does not kill the length of the note with the same veracity as these early mutes, i.e. listen to Jamerson’s note length.

Obviously when talking about this era of rock music and the bass Sir Paul looms very large. Danko certainly knew his McCartney. However, I think that regardless of that influence he comes out basically the same via his listening and cultural background.

In general, I am running into the difficulties of talking about the import of the rhythmic language of Black music because theres not really any language in the western theoretical framework to discuss it in a charitable way. Music theory fails us here. In the meantime, we will settle for words like “feel“ and “pocket” and rely on listening to the source material.

On “King Harvest” he slides into almost every note as well.

Honorary mention THE JUDGE Milt Hinton

Danko didn’t use a pick as much as many of us think though. Based on live footage I think he started using one in the second album. There are many photos by Elliot Landy of Danko playing pizzicato.

Obviously, this language is a massive part of the sound of rock music and in general is more ubiquitous than the previously mentioned two characteristics. But still, it needs mention.

By all accounts, Danko could not play the bass when he started playing it professionally in The Hawks. Stan Szelest, The Hawk’s pianist, took Danko under his wing and helped turn him into an actual bassist by teaching him boogie-woogie figures from the left hand.

Doerschuk, Robert. "Rick Danko." Van Cliburn Punched Me In The Mouth. Last modified January 20, 2021.

Honorary shout-out to Quin Kirchner whose Last Waltz tribute can certainly play the shit out of “It Could Happen to You.”

Addendum to devotion - in this era of diminishing economic outlooks it feels like we are fighting for an increasingly shrinking piece of the pie in the music “industry.” Because of this, there is a lot of focus on quote-on-quote resources. I think this is good and necessary but it is a matter of fact that we are all walking around with super computers in our pocket. That being said I don’t really think there is an excuse to not developing our relationships to the tradition.

In other words, no one knows anything about anything yet everything still sounds old. Maybe that’s why!

I think it is important to invest in these musical third spaces - song circles, bluegrass jams, and jazz sessions - to keep the algorithm out of our traditions. Playing F minor in a bar for half an hour while the local drummers blow their brains out on it is not high art, but it is an experience that every working bass player has had for the last 100 years. It is functional community building.

Theirs was not a group that was devoted to playing like an old-timey band of the 1930s — they were a rock band playing stadium arenas. They knew where they stood. There’s an element of pastiche, of course, in all of The Band’s imagery, but to them, pastiche is useful. It narrativizes history in a way that is beneficial to them in the present.

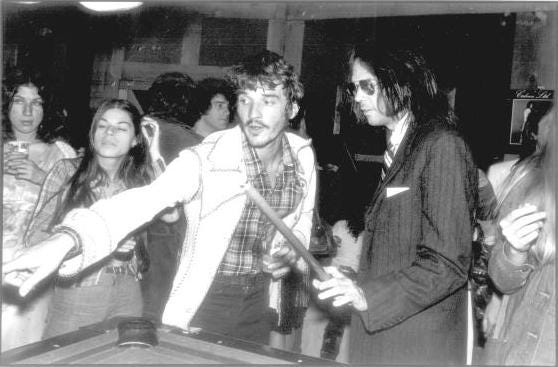

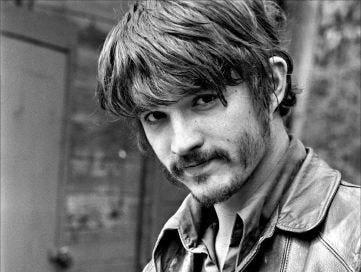

![[photo] [photo]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KD7n!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa04648c3-f423-4c7d-ad23-af4fab68552f_361x550.jpeg)

Go crazy Gus. You write like you play the bass like you roast a hog. Thankful for you brother!

Seems to me like there’s no option BUT to empty your tank any time, every time - otherwise what are you doing at all? - and that’s one of the many things I love about Rick and you.

Rick and Levon’s legacy to me is also this… SWUNG AND STRAIGHT AREN’T REAL. There’s only the song. There’s only the moment.